Capital gains represent the difference between the purchase price and the sales price of capital assets. Capital gains apply to a number of assets including: stocks, mutual funds, Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs), bonds, real estate, cryptocurrencies, stamp and coin collections, precious metals, artwork and so forth. (More specifically, if the sales price exceeds the purchase price, there is a capital gain. When the sale results in a loss, we refer to the sale as a capital loss.)

This month we’ll focus on capital gains for stock sales.

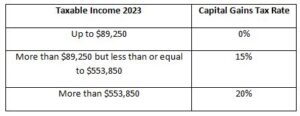

A key concept for capital gains is taxation. If you owned the asset for more than a year, capital gains rates apply. Less than a year, ordinary income tax rates apply. For most of us, the capital gains tax rate for Federal taxation is 15%, but there are actually three different rates depending upon your income. For 2023, here are the IRS rules for married couples filing jointly:

In addition, there is another tax called the Net Investment Income tax (NII). It’s a 3.8% tax applied on top of the capital gains rate. It’s dependent on your income level. For married couples filing jointly, if their Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) is more than $250,000, they are subject to this tax.

The general concept of a capital gain (loss) is pretty simple. Take the sales price minus the purchase price to determine your gain (loss). (One detail to keep in mind is that the purchase price includes and commissions and fees you paid. Similarly, the sale price excludes such costs.) The calculation of the purchase price can be a little complicated if you purchased your shares prior to January 1, 2011 (different dates for other types of investments). The reason for this is that the IRS requires brokerage firms to report your gain (loss) after that date. An additional complication occurs if you purchased stock at different points in time. Then there needs to be a determination of which shares you’re selling so that the gain can be properly calculated. There are four common ways to determine what’s called the cost basis (the purchase price of the stock you’re selling). We’ll take a look at each of these methods next.

Average Cost. This is the total amount you paid divided by the total number of shares you own. This technique can only be used for mutual funds.

First-In, First-Out (FIFO). Here you sell the shares in the order they were purchased (oldest first).

Last-In, First-Out (LIFO). The opposite of FIFO. The most recently purchased shares are sold first.

Specific Share Identification. Here you identify which shares you are selling and thereby determine their basis.

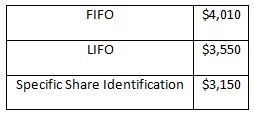

Which calculation is best depends on your particular situation. The most common way of calculating basis is FIFO, but it’s not always the best way. Here’s an example to clarify this.

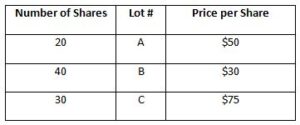

Suppose you’ve purchased shares in a company over time as follows and that you’ve held all of them over a year.

Now suppose you want to sell 70 shares and that they’re currently priced at $100 per share. The FIFO method (sell oldest first) would be:

20 shares x $50 = $1,000

40 shares x $30 = $1,200

10 shares x $75 = $750

That yields a cost basis of $1,000 + $1,200 + $750 = $2,950. The gain would be 70 shares x $100 per share (sale price) or $7,000 minus the cost basis. That is, $7,000 – $2,950 = $4,010 gain.

Using LIFO, we get:

30 shares x $75 = $2,250

40 shares x $30 = $1,200

Giving a cost basis of $2,250 + $1,200 = $3,450. This produces a gain of $7,000 – $3,450 = $3,550.

Using Specific Share Identification, let’s sell 30 shares from Lot C, 20 shares from Lot A and 20 shares from lot B. Then we get:

30 shares x $75 = $2,250

20 shares x $50 = $1,000

20 shares x $30 = $600

Giving a cost basis of $2,250 + $1,000 + $600 = $3,850. The gain on this is $7,000 – $3,850 = $3,150.

In summary, the different cost basis methods produce the following gains:

There are a couple of additional cost basis details that are worth mentioning.

Stock Splits. You need to adjust the basis for this. Suppose you had 100 shares that you purchased for $50 per share. Suppose that the stock split 2 for 1. After the split you own 200 shares and their cost basis is $25 per share.

Historical Share Prices. There are a number of ways you can determine what you paid for older shares. Here are the common ones:

- Refer to the statements received at the time of the purchase.

- Contact the brokerage company you were with at the time of the purchase.

- Contact the company that issued the shares.

- Refer to one of the online resources such as BigCharts.com, Finance.Yahoo.com or Finance.Google.com.

However you determine the price you purchased your stock at, be sure to document it for any future IRS inquiries.

You can see that determining the cost basis for your stocks can vary from totally simple (see the 1099-B form) to kind of involved (finding stock purchase prices and determining which calculation to use). There’s also the matter of offsetting gains with losses and how to treat reinvested dividends. Additionally, there is the way capital gains are calculated for your home and other assets. If you’d like to talk about cost basis, tax minimization strategies or discuss any other financial matters, we can do this in a no-charge, no-obligation initial meeting. Please visit our website or give us a call at 970.419.8212 to set up an in-person or virtual meeting.

This article is for informational purposes only. This website does not provide tax or investment advice, nor is it an offer or solicitation of any kind to buy or sell any investment products. Please consult your tax or investment advisor for specific advice.